|

||

From “The Boy’s Own Paper” 1889

Extracts from “The Boy’s Own Paper” 1870 to 1880BICYCLISTS AND BICYCLING 1 – INTRODUCTORY All doubts as to the permanency of the bicycle as an engine of locomotion have now disappeared. Many people thought that bicycling was a new fashion which would have its day like “rinking” with roller skates, and that the bicycle would become a curiosity like the “velocipede” and “dandy charger” of earlier years of this century. But it has become a fixed institution now. Bicycle clubs are in every part of the country. Bicyclists are numbered not by hundreds but by thousands. “Bicyclists”, says the “Times” in a leading article “are become a power”. They run races, with many starters, on our less frequented roads, and assemble occasionally in imposing numbers and military array at Hampton Court and other quiet localities. A procession of a thousand bicyclists is something for the imagination to fasten upon. Why, indeed, should we not have bicycle regiments to steal silently and rapidly on an unsuspecting foe ten or twenty miles off? Bicyclists are aware they run dangers, and suffer a percentage of calamities; but they have counted the costs, and found it worth while running the risk. Horses, it must be admitted, at first did not like bicycles, but neither did they like railways, and probably would like street locomotives still less. But this cannot be taken into account as any hindrance to the common use of bicycles. Horses must get used to them, as they do to many unusual objects on the streets and roads. The chief complaint against the bicycle is made on behalf of the deaf, the lame, infancy, and old age. But these are the victims of all street traffic. They ought not to cross a street without using their eyes well, exercising the greatest caution, and condescending to ask assistance. An almost superstitious terror, says the “Times”, seems to attach to the silence of the bicycle, stealing on its doomed victim, as a police magistrate observed, like a thief in the night; and when the same gentleman described this formidable object as half man, half horse, he seemed to suggest a being that the police, and even the Legislature, might not venture to cope with. For all practical purposes, however, noise is a much greater nuisance than silence, and slowness a much greater nuisance than speed. The vehicles that make streets intolerable, and that destroy life by taking away the possibility of quiet by day and sleep by night, are heavy vans driven at full speed to catch trains, huge omnibuses sometimes under like urgency, tradesmen’s carts rattling past all hours of the day, cabs as noisy as they can be made, and costermongers proclaiming their wares. On a deliberate comparison of public gain and loss, we sacrifice life, limb, and comfort wholesale to carriers’ vans, tradesmen’s carts, and omnibuses, and nobody now but a madman would attempt to make our main thoroughfares habitable, in the proper sense of that word, by rendering the street traffic less positively inimical to vitality and existence. The same must be said of bicycles. It is so great a gain to a lad if he can ride to his office on a bicycle, make a trip on it, or even a tour if he has the time, make calls, or simply indulge in the sense of rapid locomotion, that the public are bound to give him the benefit of the general rule, and put up with the chance of a few accidents. For the protection of the public there must be legislation, but much must be left unwritten law or custom. Even the rules of bicycle clubs leave some points open, and certain usages are left to the honour and good feeling of individual bicyclists. For instance, it should be reckoned a “caddish” thing for bicyclists to keep abreast of or run races with private or public carriages. It is certainly a “caddish” thing to be seen on our streets and roads on Sundays, especially when people are on their way to church. Even a Jew, if respectable, will not outrage public feeling by such “Sunday bicycling”. The beginning to learn is by no means easy work, the exertion required to keep one’s balance being considerable,

and the beginner, when he has had half an hour’s lesson, will be in as great a state of fatigue as an experienced

rider who has finished a long race. This exertion causes the pulse and respiration to be considerably quickened,

and should be risked only by those who are sound in heart and lungs. And now for a few words on tricycles. As a matter of course, the friction is greater, and requires more power to overcome it than in the case of bicycles, but power is economised by not being required for balancing. Those who are too old or nervous to mount the two wheels may ride snugly among the three with safety and great advantage to health, provided the foregoing cautions be observed. We give an illustration of the old hobbyhorse of 1812, which did fair service in its day, and also of the attempt at using the sail with our modern bicycle and tricycle, which has not been considered by practical bicyclists in any sense a success. Here, then, we close for the present, but this article is purely introductory. In our next number will be commenced a series of illustrated articles dealing minutely and comprehensively with the entire subject. They will be written by the captain of one of the crack clubs, and will supply just that kind of practical information which amateurs and learners need.

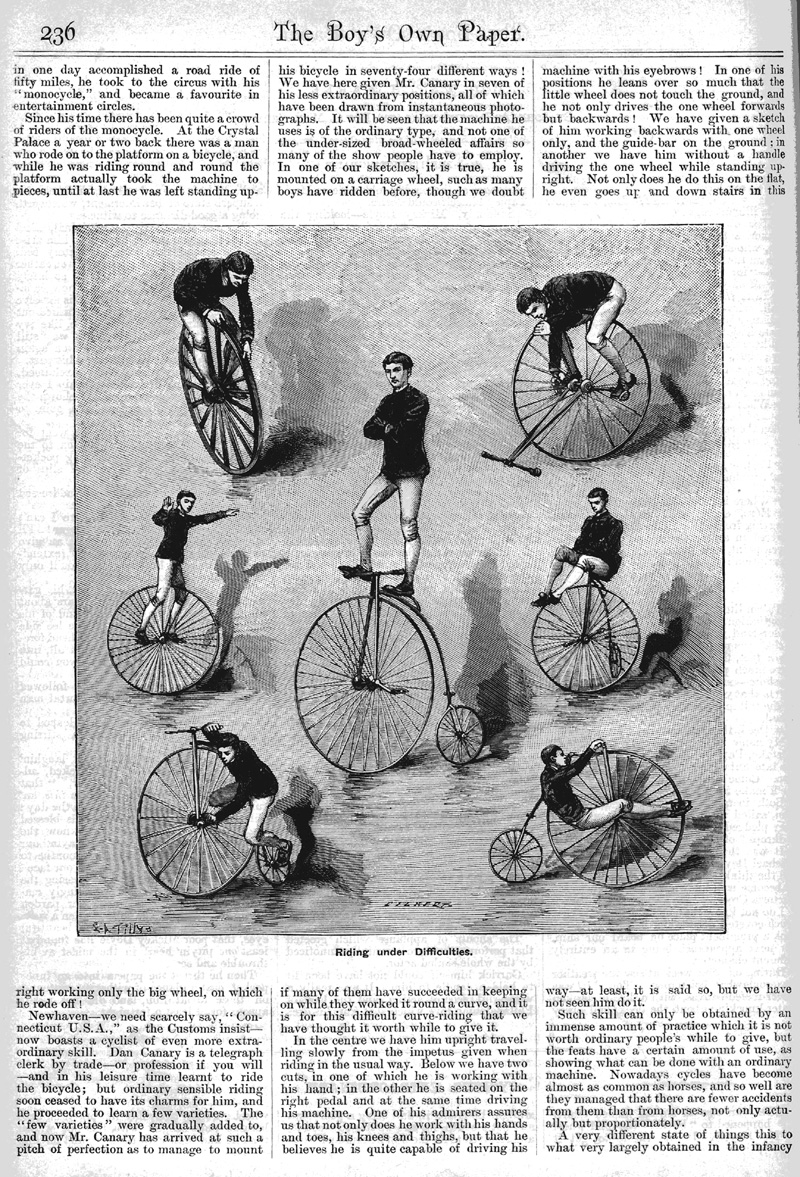

2 – Learning to Ride The art of bicycle-riding in its earlier stages is by no means difficult to acquire. In our own experience we have known bicyclists who learnt how to balance and propel the machine in the space of one lesson. As a rule, however, it will be found that it requires about three lessons before the beginner learns to use his legs. Before commencing it will of course be necessary to procure a bicycle, and if possible, also enlist the services of some good-natured friend. This, though desirable, is not indispensable. Some authorities on bicycling, in fact most, recommend the beginner to learn on a “bone-shaker”, as the old-fashioned wooden bicycle is now irreverently termed. There are objections to this, however. In the first place – and a very good thing it is, too – bone-shakers are rapidly becoming extinct, and the discomfort of bestriding one of these wretched old machines is so extreme, that it is quite enough to disgust the beginner, and make him give up the attempt to learn. We recommend the beginner to hire a small machine of modern construction, with a driving-wheel of about forty inches diameter. The usual charge made by bicycle-makers averages five shillings per week. Having procured the bicycle, the next thing is to select a quiet, secluded spot as a training-ground. This for two reasons – one being that an individual learning to ride occasionally presents himself to the public gaze in attitudes which do not always command admiration and respect; and another, that when mastering the early stages of the sport there is an almost irresistible impulse to hurl oneself madly beneath the wheels of any passing vehicle. Hence, of course, it is well to select a spot where passers-by and cabs and carriages are few and far between. It is desirable also to choose a spot where there is a gentle decline in the road with a corresponding rise, for reasons which will be explained. The first step is to wheel the machine about a bit, holding it by the handles, and noticing how it is steered by the front wheel. Next, if you have a friend with you, get him to hold the machine while you mount; and it is very essential that you should learn to mount properly at first. Take hold of the handles, place your left toe on the step, then raising your body on the left leg, slide your right leg gently over the back of the saddle, and so slip into the seat. The machine, of course, must be held by your friend at all time, otherwise you will come to grief at once. Your friend must then proceed to wheel the machine slowly along. You will find, the bicycle has an instant inclination to fall. This can only be obviated by at once turning the wheel in the direction you feel you are falling. The right amount of turn to counteract this falling propensity can only be learnt by practice, but you will soon find yourself able to gauge this, and to steer a straight course. All this time you should have been careful not to put your feet on the treadles, but now being able to balance the machine, you may begin to do so. The sensation is at first peculiar, and rather perplexing. Do not attempt to drive the machine at first; but simply allow your feet to follow the motion of the treadles as the wheel carries them round, till you get accustomed to the unusual movement. You will soon feel a desire to drive the machine by yourself. Now is the time to take the bicycle to the top of the gentle incline already mentioned. Mount properly, your friend holding the bicycle, and see what you can do by yourself. In all probability after coming to the foot of the decline you will be unable to drive the machine up the opposite incline, and the bicycle will come to the ground either on one side or the other. Throw your foot out on one side or the other, and so check the fall. In a very short time you will find you are able to get up the incline; and when you have done this you have mastered the art of driving a bicycle. The rest is but practice. You can now dismiss your friend with thanks, and practise mounting by yourself. As there is no one now to hold the bicycle while you climb into the saddle, you must contrive to make the bicycle hold itself up. To do this go to the top of our incline, and then placing your left toe on the step, and holding the bicycle as previously directed, give two or three hops with the right foot to start the machine, and when it is fairly “under way” slip carefully into the saddle. When you have learnt to do this, it is as well to discard the “hops” with the right foot, as it is impossible to render the position graceful. Instead run the machine along, and watching your opportunity to jump on the step and so swing yourself into the saddle. This looks much better, and it is not at all difficult. Having learnt to mount in an orthodox manner, the next thing to learn is how to dismount properly. In dismounting a good deal depends on the make of your machine. If the step is placed fairly high up the backbone of the bicycle, as good a way as any is to dismount by the step. To do this, take your left foot off the treadle and putting it backwards feel for the backbone with the side of your foot. Having found the backbone, slide your foot down till it rests on the step. Then resting your weight momentarily on the step, come lightly to the ground on your right foot. Most bicyclists having learnt one way of dismounting are content to stick to it, and learn no other. This is a mistake, for occasions sometimes happen when it is impossible, or almost so, to dismount in the way you have learnt. This applies more particularly to dismounting by the treadle. To do this when the left treadle is just commencing to rise, use it as if it were a stirrup, and resting your weight partly on the handles, spring from the saddle as if dismounting from a horse. This is perhaps the most favourite way of dismounting, but it is only possible to do so when the machine is going slowly. Perhaps the best way of all is to dismount by the backbone. The writer has frequently dismounted in this way when travelling over ten miles an hour. Place your left instep over the backbone, and resting your weight on it, vault backwards out of the saddle. A very effective way of getting off is to throw you right leg over the handles, and so come sideways to the ground. We have thus seen how to drive the machine, and nothing but practice is now required to render the learner an accomplished bicyclist. A few hints as to the proper movements to practise may not be out of place. We cannot too strongly impress upon our readers the advantage and necessity of learning to turn the machine quickly. It is astonishing the number of riders who profess to call themselves proficient, who are unable to turn the machine round in the width of an ordinary road. No doubt many of our readers have noticed men riding, who, having passed the turning they should have taken, are obliged to dismount, turn the machine round, and mount again. Make your curves large and fast, and by dint of practice you will find you are able to turn the bicycle in its own length. Another most important thing is yet to be learnt, and this is to ride without using the handles. The writer is not aware of any athletic exercise, unless perhaps it be lawn tennis on a very hot day, which produces, at all events when first learning, so much perspiration as bicycle riding, and you will find it necessary to use a pocket-handkerchief very freely. For this reason alone one must have one’s hands at liberty. Commence by using one hand only to steer the machine. You will find very little difficulty in this. Now take the other hand off, very carefully at first, and keep it close by to restore the balance directly you feel yourself falling. The steering as well as the driving must be done by the feet; press a little harder on the side towards which you feel you are falling, and it will have the same effect as turning the handle. To be able to ride without using the handles is a most useful accomplishment; it gives the feet a firm grip of the treadles as it were, which you will find a great benefit when riding uphill. One of the greatest pleasures in bicycle riding is running downhill, or flying, as bicyclists call it, and very like flying it is. The writer has a very vivid recollection of coming down the Hind Head, a hill three miles long on the Portsmouth road, at the rate of twenty-five to thirty miles an hour. All bicycles at one time used to be made with foot-rests, to rest the feet on when travelling down hill, and some makers still put them to their machines. This, however, is now the exception, and the usual way of descending a hill is, “legs over the handles”. To do this you must move your right hand, lift up your right leg, put it over the handle, then restore your hand, and repeat the process with the left leg. This reads a good deal easier than it is in reality, for the process requires some nerve at first. You will most likely find at first that it is comparatively easy to get up one leg, but the other seems to stick. The proper way is to throw up both legs at once; this you will find come by practice. There are, of course, many tricks which can be performed on a bicycle, such as riding side-saddle, standing on the saddle, etc. These, however, appertain more to the circus than to the road, where they are quite out of place. We will now presume our reader to be thoroughly at home on his machine. In our next article we propose therefore to discuss that most important question, How to choose a bicycle.

3 – On the choice of a machine The following are some of the best-known makers of bicycles in the market. We give all their addresses, but most of their machines may, we believe, be seen together in London at Mr. Goy’s, 21 Leadenhall Street, and 54 Lime Street EC. The Coventry Machinist Co. – address Cheylesmore, Coventry, and Holborn Viaduct E.C., supply a very excellent machine. Their specialite is the “Club” bicycle. One of the points about this bicycle is that all its parts, forks, hubs, felloes, treadles, etc., are hollow, and the back-bone is not round, but oval. It has a most luxurious spring. The spokes are attached to the hub with lock nuts. The brake is applied to the front wheel. Altogether the “Club” has many points to recommend it to the purchaser. The price, however, is rather higher than other makers. Humber and Marriott, of Nottingham, call their bicycle the “Humber”. This machine is one of the very best in the market; it would be difficult, indeed, to find its superior. There are no special features to enumerate about it, except its beauty of outline, and the very superior manner in which all its details are finished. It is, perhaps, the most popular bicycle sold, and at exhibitions takes the first place. J. Carver, also of Nottingham, styles his make by his own name. The “Carver” is in outline, almost a facsimile, of the “Humber”, the only difference being in the handles, which are pitched a little higher, not by any means an advantage. One of the special features of this make is that the spokes are hollow. Mr Carver claims that by this means extra strength is secured, while dispensing with the weight of solid spokes. Mr J. Grout – address Watson Street, Stoke Newington – is one of the oldest established makers in London. His bicycle is called the “Tension”. In the old days of bicycling it was a constant source of grief to the rider to find his spokes coming loose, and several patents were taken out to remedy this evil. Mr Grout’s idea was one of the best; but manufacturers having since discovered how to screw the spokes direct into the hub, without their coming loose under any circumstances, Mr Grout’s invention, which consists in being able to tighten up the spokes at each end, has to a certain extent become out of date. The “Tension” is now a first-class roadster, with all modern improvements, its prominent feature being its tyres, which are vulcanised on to the felloe, and cannot by any possibility come off. The Surrey Machinist Co’s works are situated at Blackman Street, Borough, S.E.. Several great novelties have just been introduced into their make, which should be seen to be appreciated. The handle is a very remarkable shape, and there is a peculiar attachment of the spring to the head, also an enormous number of spokes. Hillman and Herbert of Coventry, sell a machine called the “Premier”. This is a thoroughly good roadster, and has a very effective front-wheel brake. Singer and Co., of Coventry and Holborn Viaduct, E.C. are the makers of the well-known “Challenge” bicycle, which has long held a first place among bicycles for touring purposes. It is one of the few machines now sold which are fitted with hind-wheel brakes. By a peculiar arrangement the brake does not act on the tyre of the hind wheel, but on the ground, and is very effectual in stopping the machine. These bicycles are also remarkable for the very high degree of finish about them. Haynes and Jeffries, of Coventry, were the manufacturers of the “Ariel” and “Tangent” bicycles. The Ariel has now become very old-fashioned, and is seldom seen. Indeed, it is not now manufactured by Messrs. Haynes and Co., who trade under the title of “The Tangent and Coventry Tricycle Company”. The Ariel was one of the patents for tightening up the spokes when required, by means of a lever within the wheel. The “Tangent” is the more modern make, and is also constructed with a view to prevent the spokes coming loose. John Keen, of Clapham Junction, the champion bicyclist of England, and also a manufacturer of bicycles, calls his make the “Eclipse”. Mr. Keen claims for his bicycles that they are best for racing purposes. Great improvements have been introduced into these bicycles since they were first made, and they still hold a foremost place in the favour of bicyclists. W. Keen, of Norwood, sells a capital roadster bicycle made with hollow forks and all recent improvements. This is called the “Norwood”. The same firm manufactures the “Grosvenor”, which is claimed to be a good, strong, durable, and easy-running machine at a moderate price. J. Stassen, of the Euston Road, is one of our oldest established bicycle makers. The great feature of his make is solidity of construction, weight not being a consideration. To those who do not object to a heavy machine, and live in a district where the roads are rough, the “Stassen” will present many points of attraction. Moir, Hutchins, and Co., Queen Victoria Street, E.C., are the manufacturers of the “London”. This is a high-class bicycle, but has no particular features calling for comment. They are also the proprietors of the “Timberlake”, a machine manufactured at Maidenhead, and much patronised by Berkshire riders. It has a most effective front-wheel brake, one of the most powerful in use. Mr. Sparrow, of Knightsbridge, a veteran bicyclist, is the manufacturer of the “John o’ Great’s”. This machine has a hind-wheel brake. Mr Sparrow has a patent for attaching a strip of leather to the rubber tires, which, he says, prevents any slipping of the wheel even on the greasiest macadam. Hydes and Wigful, of Sheffield, sell the “Stanley”, a very light, strong, and elegant machine. Messrs. Bayliss, Thomas, and Co., of Coventry, are makers of the “Excelsior”. This bicycle resembles in outline the “Challenge”. It is a first-class machine, and an excellent roadster. Hinde, Harrington, and Co., call their bicycle the “Arab”. This machine has many points to recommend it. It has a powerful strap-brake applied to the hub of the driving-wheel, and is also fitted with a patent bell. In our next article we propose to give some hints on road=riding, the best kind of brakes, and how to apply them. The following are some of the best-known makers of bicycles in the market. We give all their addresses, but most of their machines may, we believe, be seen together in London at Mr. Goy’s, 21 Leadenhall Street, and 54 Lime Street EC. The Coventry Machinist Co. – address Cheylesmore, Coventry, and Holborn Viaduct E.C., supply a very excellent machine. Their specialite is the “Club” bicycle. One of the points about this bicycle is that all its parts, forks, hubs, felloes, treadles, etc., are hollow, and the back-bone is not round, but oval. It has a most luxurious spring. The spokes are attached to the hub with lock nuts. The brake is applied to the front wheel. Altogether the “Club” has many points to recommend it to the purchaser. The price, however, is rather higher than other makers. Humber and Marriott, of Nottingham, call their bicycle the “Humber”. This machine is one of the very best in the market; it would be difficult, indeed, to find its superior. There are no special features to enumerate about it, except its beauty of outline, and the very superior manner in which all its details are finished. It is, perhaps, the most popular bicycle sold, and at exhibitions takes the first place. J. Carver, also of Nottingham, styles his make by his own name. The “Carver” is in outline, almost a facsimile, of the “Humber”, the only difference being in the handles, which are pitched a little higher, not by any means an advantage. One of the special features of this make is that the spokes are hollow. Mr Carver claims that by this means extra strength is secured, while dispensing with the weight of solid spokes. Mr J. Grout – address Watson Street, Stoke Newington – is one of the oldest established makers in London. His bicycle is called the “Tension”. In the old days of bicycling it was a constant source of grief to the rider to find his spokes coming loose, and several patents were taken out to remedy this evil. Mr Grout’s idea was one of the best; but manufacturers having since discovered how to screw the spokes direct into the hub, without their coming loose under any circumstances, Mr Grout’s invention, which consists in being able to tighten up the spokes at each end, has to a certain extent become out of date. The “Tension” is now a first-class roadster, with all modern improvements, its prominent feature being its tyres, which are vulcanised on to the felloe, and cannot by any possibility come off. The Surrey Machinist Co’s works are situated at Blackman Street, Borough, S.E.. Several great novelties have just been introduced into their make, which should be seen to be appreciated. The handle is a very remarkable shape, and there is a peculiar attachment of the spring to the head, also an enormous number of spokes. Hillman and Herbert of Coventry, sell a machine called the “Premier”. This is a thoroughly good roadster, and has a very effective front-wheel brake. Singer and Co., of Coventry and Holborn Viaduct, E.C. are the makers of the well-known “Challenge” bicycle, which has long held a first place among bicycles for touring purposes. It is one of the few machines now sold which are fitted with hind-wheel brakes. By a peculiar arrangement the brake does not act on the tyre of the hind wheel, but on the ground, and is very effectual in stopping the machine. These bicycles are also remarkable for the very high degree of finish about them. Haynes and Jeffries, of Coventry, were the manufacturers of the “Ariel” and “Tangent” bicycles. The Ariel has now become very old-fashioned, and is seldom seen. Indeed, it is not now manufactured by Messrs. Haynes and Co., who trade under the title of “The Tangent and Coventry Tricycle Company”. The Ariel was one of the patents for tightening up the spokes when required, by means of a lever within the wheel. The “Tangent” is the more modern make, and is also constructed with a view to prevent the spokes coming loose. John Keen, of Clapham Junction, the champion bicyclist of England, and also a manufacturer of bicycles, calls his make the “Eclipse”. Mr. Keen claims for his bicycles that they are best for racing purposes. Great improvements have been introduced into these bicycles since they were first made, and they still hold a foremost place in the favour of bicyclists. W. Keen, of Norwood, sells a capital roadster bicycle made with hollow forks and all recent improvements. This is called the “Norwood”. The same firm manufactures the “Grosvenor”, which is claimed to be a good, strong, durable, and easy-running machine at a moderate price. J. Stassen, of the Euston Road, is one of our oldest established bicycle makers. The great feature of his make is solidity of construction, weight not being a consideration. To those who do not object to a heavy machine, and live in a district where the roads are rough, the “Stassen” will present many points of attraction. Moir, Hutchins, and Co., Queen Victoria Street, E.C., are the manufacturers of the “London”. This is a high-class bicycle, but has no particular features calling for comment. They are also the proprietors of the “Timberlake”, a machine manufactured at Maidenhead, and much patronised by Berkshire riders. It has a most effective front-wheel brake, one of the most powerful in use. Mr. Sparrow, of Knightsbridge, a veteran bicyclist, is the manufacturer of the “John o’ Great’s”. This machine has a hind-wheel brake. Mr Sparrow has a patent for attaching a strip of leather to the rubber tires, which, he says, prevents any slipping of the wheel even on the greasiest macadam. Hydes and Wigful, of Sheffield, sell the “Stanley”, a very light, strong, and elegant machine. Messrs. Bayliss, Thomas, and Co., of Coventry, are makers of the “Excelsior”. This bicycle resembles in outline the “Challenge”. It is a first-class machine, and an excellent roadster. Hinde, Harrington, and Co., call their bicycle the “Arab”. This machine has many points to recommend it. It has a powerful strap-brake applied to the hub of the driving-wheel, and is also fitted with a patent bell. In our next article we propose to give some hints on road=riding, the best kind of brakes, and how to apply them.

Bicycle, by a recent decision in the Courts of Justice, having been declared to be a carriage, and as such bound to obey the rule of the road, bicyclists cannot be too careful in obeying the regulations laid down by authority to be observed on the Queen’s highway. Never pass a vehicle on the wrong side. There is nothing which causes so much antipathy among drivers against bicycles as having one flash past them on the wrong side. The horse, or horses, do not expect it, and in consequence are apt to shy. Should any damage be thus caused, the bicyclist, by the recent decision, is liable for the whole amount. It is well also, when overtaking a vehicle, to give notice that you are about to pass; and when meeting a carriage, should the horse show any signs of restiveness, by all means dismount. Horses are becoming used to the sight of bicycles, and it is now rare to find an animal shy at the sight of one. It was not so once. The new regulations just issued by the Highway Board provide that every bicycle must carry a lamp after dark, showing a bright light, and also a bell. The rider must therefore equip himself with these articles. Lamps are made either to fit on the head of the machine, or to fix on the hub between the spokes. Those which are attached to the hub appear to be now the most fashionable, but those which are screwed to the head of the bicycle decidedly give more light, as a larger lamp can thus be carried. The spokes in the most recent makes are so numerous that it is not possible to pass a large lamp through them, in order to attach it to the hub. The best kind of bell to get is one that can be sounded at pleasure. The constant tinkle-tinkle of the ordinary small bell is most wearying. The “Pegasus” stop-bell is a very good invention. It is made in the shape of the ordinary bell, but by pressing a small slide, or pulling it out, it either rings or is silent at the will of the rider. The ”Arab” bell is attached to the head of the machine over the driving-wheel. It is in shape like a gong, and is set in motion by a small lever worked from the handles. The clapper is set going by the passing spokes, producing something like 2,000 strokes a minute. A great many bicyclists carry bugles, presumably to announce their approach. This practice cannot, however, be commended, and is only tolerable when the rider is able to blow decently. The spectacle of a bicyclist managing with difficulty to produce from time to time some fearful and wonderful notes on his instrument apparently for his own enjoyment, for it can please no one else, is not edifying. A loud-sounding whistle, like those used by tramcar-drivers, is perhaps the best thing to use to clear the road, or when passing a vehicle. Always ride up every hill you can; one of the greatest pleasures in road-riding is the feeling that you have conquered a hill, which perhaps sometime back you had to dismount for. You should always try and avoid all appearance of labour when riding uphill. Nothing impresses an outsider so much as seeing a bicyclist easily and swiftly surmounting a steep hill. Sit as upright as you can, and don’t double yourself, as some do, almost into the shape of a right angle. Nothing is gained by it. Always dismount if you feel the hill is becoming too much for you. It is not worthwhile to have managed to get to the top of the hill, and then find, on descending the other side, that your exertions have brought on cramp. The writer has a very ugly recollection of such an event happening to him, when riding one very muddy day in winter on the Portsmouth road. He had ridden with great exertion up one of the stiffest hills on the road, the work being made harder by the thick mud. On preparing to descend the other side, he found himself attacked with cramp in both legs. To this day he hardly knows how he managed to get off the bicycle, as both legs were for the time useless. When riding in a strange country, over roads you have not travelled before, caution should be observed in going downhill. Never let the machine go till you can see the bottom of the hill. It is very unpleasant, when the bicycle is fairly running away with you, to come suddenly across a closed railway-crossing or turnpike-gate; some of these obstructions are often found half-way down a hill, notably at Reigate and elsewhere on the Brighton road. All roadster bicycles should be provided with ample brake power, either to front or hind-wheel. The front-wheel brake is now the most popular, and in the hands of a good rider is undoubtedly the safest. The worst point about the hind-wheel brake is that it must be applied by means of a cord or chain, which is at any moment liable to snap. The front-wheel brake being applied by a lever directly from the handles, there is no fear of such a possibility happening. Care must be taken not to put a front-wheel brake on too hard at first, as it will inevitably cause the bicycle to kick and throw the rider. It must be applied gradually, the rider at the same time leaning his body back, so as to throw his weight on the hind wheel. Front wheel brakes are either roller or spoon. The first has a small revolving roller which acts on the rubber tyre, and is supposed not to wear it away so much as the spoon when the iron acts on the rubber direct. Practically, however, it is not the rubber which suffers, but the brake, the rubber being the stronger of the two. The roller brake throws up more dirt than the spoon does. The “Timberlake” front-wheel brake is one of the most powerful in use. The brake consists of a small piston fitted with a roller which acts on the tyre. One side of the piston is fitted with a rack into which fits a pinion revolved by means of the handles. By simply turning the handles the brake is thus either raised or lowered. The “Stassen” brake is also worked with a piston, but instead of a rack and pinion it is set in motion by an eccentric attached to the steering bar, and revolved by the handles. Nearly all the other front-wheel brakes in use are either thumb or lever brakes. Ever bear in mind that the use of a brake is to keep the machine under control, and not to pull it up if it has run away with you. A proper attention to this maxim would avoid many accidents. Carelessness is generally the cause of accidents in everyday life, and it certainly contributes more towards croppers than anything else in bicycling. Many fellows when they are mounted on bicycles seem to abandon all the ordinary precautions they observe when engaged in other athletic amusements, and the consequence is they are continually coming to grief. It should be and is much safer to bicycle than to hunt, and properly managed a bicycle is a safe a mode of locomotion as any other. When starting on a run you should always see that all the nuts, saddle, screws, etc, are tight and well set up. Never stir out without your spanner and oil-can. It is most annoying when you have gone some distance to find a nut loose and have no means of tightening it. Always keep your bicycle thoroughly clean; a rusty machine looks very bad indeed. When riding always wear shoes, they look very much better than boots. Knicker-bockers or breaches for bicycle-riding should be lined with wash leather. Grey is the best colour for a bicycle suit, as it does not show the dust, though dark blue looks very nice. It is well to have plenty of pockets in your coat, with a small pocket specially made for the oil can, and lined with leather; it is much handier when requiring to “oil-up”, than having to get the can out of the saddle bag. Never ride on the path. It is, we must confess, very tempting when the roadway is stony and muddy, but still it is not the right thing to do, and often brings bicycling into disrepute. Some bicyclists are too apt to shout unnecessarily, and seem to enjoy giving a shock to people’s nerves. Bicycling is no doubt more enjoyable when riding in company. Always select, if possible, for your companion at first, a rider very much your superior in skill. There is nothing like emulation for causing progress. Do not attempt too long rides at first. It is only when one is in fairly good training and practice that the long rides described in the bicycling press can be accomplished. Thirty miles will be quite enough for your first trip,

5 – Touring Touring may fairly lay claim to be called the backbone of bicycling; for whilst bicycle racing undoubtedly brings the sport more prominently before the public, bicyclists who race are happily most decidedly in the minority compared with the great army of riders who have explored on their machines all parts of England, and nearly every practicable road abroad. Touring on a bicycle is without doubt the most independent means of locomotion extant; there are no time-tables to consult, no Bradshaws to be puzzled over, no personally conducted parties; the bicyclist is emphatically his own master and has the satisfaction of knowing that should he elect to prolong his stay in any place, no horse is eating its head off in the stable, while his bicycle is ready, with the expenditure of a little oil, to convey him wherever his fancy or his convenience may direct. Tours on bicycles may be described under two headings – firstly, those which do not extend over two days; and secondly, those more prolonged trips occupying a week or more, according to the time at the rider’s disposal. The first division embraces more particularly those tours called Saturday to Monday runs. Some of the most enjoyable journeys in the neighbourhood of the metropolis can easily be accomplished between mid-day on Saturday and early on Monday; with a quiet, restful Sunday, and service at some pretty country church. Makers of appliances for touring purposes fully discriminate between the above-mentioned tours in the matter of luggage, supplying what they call long and short-journey bags. The question of luggage is a most important one in connection with touring on a bicycle. When the duration is extended beyond a week it becomes necessary to consider how best to carry, as the Romans wisely termed it, one’s “impediments”. All luggage is best carried on the bicycle itself. Some riders adopt the expedient of carrying an ordinary tourist knapsack strapped on their back, but this is very unsightly, and is decidedly the most inconvenient method. There are three methods of securing luggage to a bicycle; the first is to carry it behind the saddle; the second in front of the handles; and the third – strange as it may sound – inside the spokes of the front wheel. Mr Stassen, of the Euston Road, is the inventor of the last-named method, and has taken out a patent for a bag which fits round the hub of the driving wheel. Though ingenious, this method cannot, to our thinking, be commended. In the first place the bag has to be packed when it is inside the wheel, and it is very often most inconvenient to have to do one’s packing and unpacking in the stable yard, while the appearance of the bag when packed inside the wheel is not good. Luggage when carried in front of the handles is placed in a small valise, which is strapped on to a small metal framework attached to the steering-bar. This method also has its drawbacks. In the first place the appearance is not elegant, and unless balanced by a bag behind the saddle, renders the machine top-heavy. The best way of all to carry luggage, according to our experience, which has been pretty extensive in such matters, is behind the saddle, and for this purpose the best bag is that known to bicyclists as the M.I.P., or multum in parvo. It is not generally known that the bicycling world is indebted for this invention to Mr Ruecker, late captain of the London Bicycle Club. It is in shape of an oblong bag about fourteen inches long, seven wide, and four deep. It is attached to the saddle by two swivels, and is prevented from slipping by a clip which fits over the spring, and is not at all in the way of mounting and dismounting, even when filled to its utmost capacity. When supplemented by a small bag in front of the handles, enough luggage can by this means be carried to last the rider from a fortnight to three weeks. Some bicyclists send on their luggage by train to the destination they propose arriving at; but this means they are as much bound to reach the place as the train itself, thus depriving bicycling of its greatest pleasure, the power to stop where one likes. It is impossible to procure too good a bicycle for touring purposes. A machine which is intended to convey the rider over many scores of miles of varying roadway at a high rate of speed, must be constructed in the very best manner to secure that degree of comfort and safety which is so eminently desirable on a bicycle tour. In old accounts of bicycle journeys it is most common to read of tyres coming off, spokes coming out, backbones breaking, and other similar disagreeable breakdowns. Modern makers are fairly entitled to say Nous avous change tout cela. And, accidents excepted, all such inpleasant incidents as those indicated are now unfrequent. In our experience we have always found it wisest in the long run to stop at the best hotels, the charges being rarely higher than those made in second-rate inns, while the accommodation is of course much superior, the highest charge the writer ever paid for a night’s lodging being at a wretched little inn on the banks of the Thames, where the bill was at the rate of about thirty per cent more than the charge for the same accommodation on the preceding night at one of the best country hotels in England. Bicycle touring, whilst perhaps the cheapest method of seeing the country, cannot, of course, be done for nothing. Ten shillings a day will generally be found ample to defray one’s expenses, providing one is not troubled with too expensive a thirst. Referring to this topic, it is well to observe that the less one drinks the better. The best and cheapest thirst-quencher is lime-juice mixed with a little water. There are in most towns in England at the present time, hotels which specially cater for bicycle tourists. This arrangement has been brought about by means of an association called “The Bicycle Touring Club”. List of these hotels can be obtained from the secretary of the club. The expenditure necessary to join this club being very small, it is worthy the attention of intending tourists, as in nearly every town there are “consuls” of the club, as they are called, who are always ready and willing to afford bicyclists every information in their power respecting the roads, hotels, etc., in their immediate neighbourhood. It is well to make a tour, the duration of which is not intended to extend over two days, “circular”. A greater variety of country can thus be covered. It is, perhaps, an open question among bicyclists as to the amount of ground that can be got over with comfort on a bicycle during a day’s ride. If the rider desire to stop for the inspection of any places of interest during the day’s ride, we should consider forty to fifty miles a very fair day’s run. There are many riders who would consider that looking at old monuments was a great bore, and that the great enjoyment of bicycle touring is to get over the longest distance in the shortest time. Some very wonderful rides of this nature have been accomplished. The season before last a friend of the writer’s rode from London to Bath and back, a distance of 220 miles, in the twenty-four hours. This was, of course, an exceptional feat. Bicyclist residing in the country undoubtedly have a great advantage over their confreres in London or its immediate neighbourhood, in that they get on to good roads when starting from their own doors. All the roads leading out of town are for some considerable distance more or less bad for bicycling, and till the macadam is left fairly behind one, the pleasure of riding can hardly be said to begin. In attempting a circular run it will be well, therefore not to make London a starting-point, but to select a spot outside the metropolitan radius. The south-west of London is perhaps most favoured by metropolitan bicyclists, though there are several influential clubs which have their headquarters in the north, notable among them being the Pickwick, the oldest established club. The road to Brighton is very popular, and as most riders select this for their first trip, we will give some notes on the various routes thither, of which there are no less than six – viz., Redhill, Reigate, Lingfield, East Grinstead, Horsham and Chorley. The longest way is by East Grinstead, the shortest by Redhill, fifty-eight and fifty-one miles being the respective distances. The road via East Grinstead cannot be recommended except for the sake of paying a visit to the Railway Hotel at this place, one of the most popular hostelries frequented by bicyclists. This road is extremely hilly and bad. The best scenery is on the Horsham road, but we should recommend the route via Reigate. Starting from Westminster Bridge, the road lies through Tooting and Mitcham to Sutton, all more or less bumpy macadam. It is mostly up-hill work from here to Reigate Hill. Very great caution must be observed in descending this hill, and we would strongly advise all riders who do not know the road thoroughly to get off and walk before coming to the Suspension Bridge, as it is one of the worst hills in Surrey. You can mount again on coming to the turnpike half way down. After leaving Reigate, there is a nice level run of about six miles to Crawley. Four miles beyond Crawley is Handcross, and there are two roads to Brighton from here, one by Bolney, the other by Clayton, which is the better of the two. There is a long hill over the downs by Clayton Tunnel, which most men will walk up, but on reaching the top there is a splendid run down-hill nearly all the way into Brighton. There is, of course, an immense number of hotels in Brighton, offering any amount of accommodation, but we

strongly recommend the Old Ship; it is well patronised by bicyclists, and the charges are moderate. Ripley is a delightful country place, six miles from a railway station, consequently free from excursionists. From Ripley to Guildford the road is splendid – six miles of the best roadway in England. There is a steep hill down into Guildford, dangerous unless with a very powerful brake. Take a left-hand turning at the bottom, thence through Godalming and Milford to the Hind Head. Three miles of up-hill work here; a most splendid view from the summit, thence into Liphook, through Petersfield and Horndean, to Cosham. All good surface, but hilly. The last bit of road into Portsmouth is not good. The Sussex at Portsmouth is a good hotel and can be recommended. The road from London to Bath is one famous in the annals of bicycling, the London Bicycle Club holding their annual 100-mile road race over this course, on which some wonderful times have been done. The Bath road, though exceptionally good in parts, notably between Hungerford and Newbury, is in some places bad, especially between Slough and Maidenhead, in very dry weather. It is on the whole one of the most level roads in England, and used to be popular on account of this quality in the days when men were not so good at hill-riding as they are now. The road to Yarmouth is very popular among bicyclists, especially those residing in the east of London. We should advise any one going the journey to take the train from Liverpool Street as far as Romford, for the main road from London to this place is very bad riding; but from here through Brentwood and Ingatestone to Chelmsford it is very good, and continue so through Witham and Kelvedon to Colchester. The last time the writer travelled over this road he accomplished the distance between Romford and Woodbridge, sixty-five miles, in five hours and twenty minutes, including all stoppages. This was with the help of a very strong wind; still it will give some idea of the general goodness of the road. Before coming to Woodbridge we pass through Ipswich, and have a long hill to climb going out of the town. After Woodbridge the road passes through Wickham Market, and Saxmundham to Wangford; from here to Yarmouth is twenty miles, the road throughout being very good, with the exception of the last two miles. The main road from London to Manchester, 186 miles, may be described thus: good to Dunstable; between here and Northampton pretty good but hilly; from here to Market Harborough good, but still hilly; here to Derby through Leicester very good. Through the Peak district to Buxton is lovely scenery, but the roads are not particularly good, and between here and Manchester they are in places very bad. For those of our readers who think of starting on a long straightaway journey we can recommend the road to the Land’s End. There are some tremendous hills to be encountered, so it is imperative that plenty of brake power be provided. The total distance is 288 miles. The road is fairly level, but rather rough to Hounslow. Here, taking the left hand, it is level to Staines, but generally dusty in summer and heavy in winter, the road being gravel. Thence to Egham is heavy sand, but then up Egham Hill, a good hard gravel road, tolerably hilly, leads past Virginia Water through Bagshot. From here to Dorchester the surface, on the whole, is excellent and though after Andover there is hardly a continuous mile of level, there are not more than four or five unridable hills of any length. Dorchester to Bridport starts with a two-mile ridable incline, and after some short pitches a very steep hill at Long Bredy, near Winterbourne Abbas, is reached. Thence to Bridport is hilly, and rough in places. Thence it is pretty level. Another two-miles incline out of town, but the surface is excellent, and, indeed, continues good all the way to Exeter, being formed of flint. Near Chideock it is very hilly; the same near Charmouth, but a little less hilly on to Axminster. Very rough hill down into Honiton, but thence fourteen miles of very good going into Exeter, except about two miles near Fenny Bridges. A steep hill out of Exeter is unridable, and the descent on the other side is as bad. A series of similar hills, loose and flinty, continue to Oakhampton; thence the road, though hilly, is excellent to Launceston. Thence on to Bodmin is very hilly, and continues so for ten miles beyond; but from here to Truro the road improves. Truro to Penzance is very fair except the last two miles. The road from Penzance to Land’s End is very bad indeed. It is not of course possible, within the limits of an article, to do more than describe briefly just a few of the roads of England. There is nothing like exploring the country for oneself. A copy of Carey’s Book of Roads is a first-rate manual to have by one. It is not published now, and can only be purchased second-hand. The Coventry Machinists Company publish a book of roads something on the same plan, and it contains much useful information. A good map of England showing the roads should also be purchased. It is wonderful how useful a bicycle is in instilling a knowledge of practical geography, and it is undoubtedly the fact that thousands of young men have in this way acquired a knowledge of their own country, of which, without a bicycle, they would have remained forever ignorant.

6 – Clubs Rather lengthy controversy was carried on some months ago in the “Bicycling News”, as to the desirability of a bicycle rider joining a bicycle club, or remaining unattached. The central point of the argument was – Are bicycle clubs necessary, or are they not? “A bicycle” – so argued the anti-clubmen – “can only be ridden by one man, and is essentially an instrument of solitary enjoyment. Therefore, as men can enjoy all the pleasures of bicycle riding without belonging to a club, the necessity for a club does not exist”. An answer to this argument may be found in the case of the Royal Canoe Club. A canoe can only be paddled by one man, but it remains an undoubted fact that the present position of canoeing is due to the exertions of the Royal Canoe Club; and similarly both bicycles and bicycle riding have reached their present state of perfection through the influence brought to bear upon the sport by bicycle clubs. It would, moreover, be unnatural that, as every branch of amusement and science, from archery to zoology, has its club, bicycling should not be represented in the world of clubdom. Whenever men have a kindred amusement, it will always be found that sooner or later they form themselves into a society or club for the purpose of furthering their common enjoyment. A man belonging to a bicycle club has the opportunity of examining and trying all the varieties of bicycles ridden by his brother members. This is in itself no small advantage; he has also the opportunity of improving his riding with the aid of the wrinkles which in club companionship he is sure to pick up. Then, too, if inclined to try his fortune on the racing-path, there are the club prizes to be competed for. One of the advantages of a club is the opportunity it offers to obtain companions on intended tours: and now that the Bicycle Touring Club has come into existence, this advantage is largely increased. We have as yet said nothing about one of the great institutions of bicycle clubs – club runs. We venture to think – though, in the position which we occupy, it is, perhaps, heresy to do so – that club runs are, to a certain extent, a mistake. It may be asked, What is a club run? In answer to this question we will give the following description. At an appointed hour on Saturday afternoon – usually 3 or 4pm, the members of the club are invited to assemble at headquarters to take part in a run to a destination determined on beforehand by the committee. All the members present having taken their places two and two, the procession, headed by the captain, or deputy captain, starts, and proceeds along the road in a more or less straggling manner till the destination, generally some country inn, be reached. After partaking of refreshments, which usually take the shape of tea with eggs, and indulging in some harmony in the back parlour, lamps are lighted for the return journey, and the procession goes homeward. Now, as the number of places which can be visited in the course of a Saturday afternoon is, to a certain extent, limited, runs are apt to be repeated; the same songs, too, after a time, grow monotonous, and one becomes inclined to say that life is not all tea and eggs. The older a club gets, the more do the attendances at its club runs fall off. We are aware there are exceptions to this rule, but it may be generally taken to be the case. Club runs are always better attended in the early spring. After a winter’s rest, men get rusty in their riding, and are satisfied with the comparatively short distances covered by club excursions. As the season goes on, and they get into practice again, they want to go further afield; and now the great enemy to club runs – namely, race meetings – steps in. In many clubs a prize is given to the member who has attended the greatest number of these Saturday afternoon excursions. Many club officials seem to think that men quite commit a crime if they absent themselves from the runs fixed on by the committee. It, however, stands to reason that if club runs were on all occasions attended by the full strength of the club, they would become such a nuisance that the public would not tolerate them. A procession of ten to twenty bicyclists does not interfere very much with the public traffic, but as several of the metropolitan clubs number from fifty to two hundred and fifty riders, imagination fails to depict the possible consequences of such a string of men on wheels crowding the roads every Saturday afternoon. The increase in number of bicycle clubs, both metropolitan and provincial, has been phenomenal. In 1874 there were in London eight clubs; in the provinces eleven. In 1878 there were in London sixty-four clubs; in the provinces one hundred and twenty-four. During the last two years these numbers have been very largely increased. The club which boasts the greatest number of members is the Cambridge University Club, containing in its ranks no less than 254 active members. This great increase in the number of clubs cannot be considered an unmixed benefit for the sport of bicycling. Many of the clubs are numerically very weak, one club within the writer’s knowledge containing four members only. It would be decidedly better if men, instead of forming a small new club, would first see if there is no old-established club in their own neighbourhood which they might join. The interests of bicycling are better served by a smaller number of large and powerful clubs than by a greater number of small and insignificant institutions. Bicycle racing has admittedly reached its present state of perfection through the instrumentality of the leading bicycle clubs. In 1874 there were only two bicycle clubs which held race meetings. Last year in London alone there were thirteen race meetings promoted by the metropolitan clubs, at which prizes to the value of hundreds of pounds were presented for competition. To clubs, too, we are indebted for the best, and most serviceable riding-costume. It is generally easy to distinguish between the club man, in his smart and neatly-fitting uniform, and the unattached rider, dressed, as a rule, in all the colours of the rainbow! Before concluding, this article on clubs, we must not omit to mention the great gathering of metropolitan clubs

which takes place annually at Hampton Court. In 1876 some thirty or forty riders gathered together, and rode in

procession through Bushey Park. In 1877 the number had increased to 300. Last year it is estimated there were over

2,000 riders present. The meet is arranged to take place this year on May 22nd at 5pm, when probably a still

greater number of bicyclists may be expected to be present. It very often happened that though a man might be an excellent rider, he was in other respects not suited to hold the position of captain of his club. The duties of the captain of a bicycle club are rather onerous. On all excursions by the club he takes command, and presides at all committee meetings. His position demands much tact and discretion, it being no easy task in a club run to keep the members well together. There are always some men who want to race on in front, while others show a great inclination to walk up some of the hills and so keep the rest back. To reconcile the two opposing influences is one of the most difficult duties the captain has to perform. It is essential also that the captain should possess some knowledge of the proper manner of conducting the club business at committee meetings, and so avoid much of the waste of time which is often caused by the inexperience of young members of the committee. The officials of a bicycle club are, usually, president, vice-president, captain, deputy captain, secretary, and treasurer. These, with four or five outside members chosen to serve on the committee, form the governing body of the club. The presidents and vice-presidents are generally ornamental; in cases of local clubs it is usually the mayor, and other persons of importance in the neighbourhood, who are invited to fill such offices. The captain has already been alluded to. The duties of deputy-captain are sufficiently explained by the name. On club runs, when the captain is present, the deputy-captain always rides last. Should the captain not be present, the deputy-captain takes his place, appointing some other member as deputy-captain pro tem. The post of secretary to a bicycle club is a very important one, requiring much punctual attendance to club business, combined with much affability, and what the French term savoir faire. The mode of joining a bicycle club is, of course, as in other clubs, by election. Members are usually balloted for fortnightly, one black ball in five excluding. Intending members must be proposed by one member and seconded by another. Some clubs are much more exclusive than others, for bicycle clubs are not exempt from the ridiculous feeling which pervades to a great extent athletic clubs – that if a man be “wholesale” he is a gentleman, but if “retail” he must of necessity be a cad; and while members have the greatest reverence for a man who sells tea by the chest, they entertain nothing but contempt for the man who retails it by the pound. The following is a brief description of some of the principal bicycle clubs in the metropolis. First on the list comes the London. This club holds the wholesale versus retail theory very strongly; therefore we will advise intending members, should they come under the latter category, not to incur the risk of rejection by trying to join this club. The London has the largest number of members of any of the metropolitan clubs. As its members reside in all parts of London and the suburbs, it is found impracticable to have one common rendezvous on a Saturday afternoon, so that the club is divided into five divisions – the west, the south-west, the south-east, the north-west, and the north-east. Each division is practically a separate club, having its own captain and deputy-captain. The club uniform is dark grey, with dark brown stockings and black polo cap. The Temple Club is the next largest club to the London. The members of this club are not recruited, as would seem to be implied by the name, from the ranks of lawyers and barristers in the Temple. This club is also divided into districts like the London; their central place of meeting is the Temple Railway Station, on the Thames Embankment. The uniform is a light brown check, polo cap, and stockings of the same colour. The Pickwick Bicycle Club is the oldest established in London; the headquarters are in the neighbourhood of Hackney. Each member of this club has, we believe, on joining to assume the name of some character mentioned in the “Pickwick Papers”, and a few years ago it was customary for them to enter for bicycle races under their assumed names. Referring back to some old reports of race meetings, we find the name of the “Fat Boy” frequently mentioned. As may naturally be supposed, this name was appropriated by one of the thinnest of men. He is still racing with success under his real name. The club uniform is dark blue, with the initials of the club in yellow on the cap. The Surrey Club comes next in seniority to the Pickwick. This club has long held a great reputation for racing, and its race meetings, held at the Surrey Oval, are always the most successful of bicycle reunions. The captain of this club, Mr Osborne, is perhaps the finest amateur road-rider in England, and has long been proverbial for skill in hill-riding. The uniform of the Surrey is grey, with a black band round the polo cap. The Wanderers Bicycle Club has its headquarters at the Alexandra, on Clapham Common. This club is noticeable for the capital manner in which its club runs are attended, seldom less than a score of members turning up for club evenings. Mr Cortis, the amateur champion, is a member of this club, and, owing to his extraordinary performances on the racing-path, has done much to bring the name of his club before the public. The uniform is dark blue, with a small badge worn in the button-hole of the coat. The “Kingston Club” is an old and well-established one. The headquarters are the Assize Courts, Kingston. This club ought to produce plenty of good racing men, one of the best cinder-paths in the neighbourhood of London having been recently opened in Kingston. The uniform is dark grey with blue cap and stockings. The silver badge is one of the prettiest we have ever seen, consisting of a combination of the club monogram and the borough arms. The West Kent is a rising and important club. The Right Hon. Robert Lowe is a member, and so, we believe, was the late Prince Imperial. In allusion to the lamented prince, the writer remembers seeing him driving his bicycle, in 1868, up and down the broad asphalte pathway in front of the Palace of the Tuileries at Paris, little dreaming of the great changes which were to occur in his fortunes. The Atlanta is a flourishing young club. The zeal its members display is unbounded. It is, we believe, the only club which has a fixture for every Saturday throughout the year, summer and winter. The Uniform is dark blue, with a stand-up collar and helmet. At the last Hampton Court meet the remark was made apropos of this club, “Here come the Bobbies!” The “Druids Club” was, we believe, originally intended to be only open to youths under eighteen years old. We are not quite sure why the name Druids was adopted, unless it was that Druids were generally very old men. Mr Hamilton, of this club, is one of the most promising racers of the day. The Stanley Club has its headquarters at the Athenaeum, Camden Road; the secretary is Mr Hutt, a gentleman of remarkable enterprise. He has been instrumental in promoting some most successful exhibitions of bicycles and bicycling appliances. The last show was held at the Town Hall, Holborn, in the early part of this year, and was the most interesting and successful exhibition of the kind ever held. The uniform is dark blue, with blue helmet and club badge. There being over sixty clubs in London and the suburbs, it would be impossible to describe them all. Suffice it to say that if any of our readers are meditating joining a club we would, generally speaking, recommend them to choose an old and well-established institution instead of belonging to the local club. | ||

|